Aboriginal Heritage

Shark Bay is the traditional country of three Aboriginal language groups: Malgana (Centre), Nanda (South) and Yinggarda (East coast). The Malgana name for Shark Bay is Guthaaguda, a place of two waters.

There are about 130 registered Aboriginal heritage sites in the Shark Bay area including quarries, rock shelters, burial sites and large scatters of discarded shells, bone and other food-related artefacts known as middens.

Archaeological sites around Shark Bay tend to be close to the shoreline. Edel Land was a particularly important place for early Aboriginal people with a stone quarry at Crayfish Bay, fresh water at Willyah Mia on Heirisson Prong, and numerous middens and camp sites. There is also a burial site at Heirisson Prong.

Peron Peninsula was also important with middens found at many locations including Cape Peron, Cape Rose, Goulet Bluff and Eagle Bluff. Camp sites, water wells, fish traps and grinding grooves are also scattered across the peninsula. Excavation of a cave at Monkey Mia revealed the remains of molluscs, cuttlefish, crabs, dugongs, turtles and fish.

Stone for spears and tools was quarried on the western coast of Shark Bay at Crayfish Bay, and on the eastern coast at Yaringa near Gladstone.

All Aboriginal sites and artefacts are protected by the Aboriginal Heritage Act. It is illegal to disturb these places.

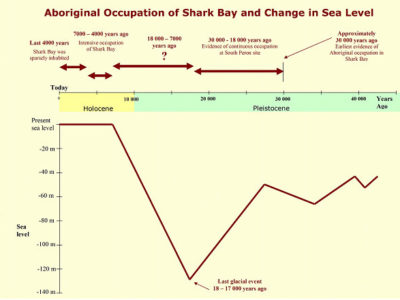

Aboriginal people first inhabited Shark Bay some 30,000 years ago and moved to and from the area in response to changing sea levels and availability of fresh water and food.

A site near Eagle Bluff shows two periods of occupation, the first during the late Pleistocene between 30,000 and 18,000 years ago, and then during the Holocene about 7,000 to 6,000 years ago.

Sites at Monkey Mia and Useless Loop show the current period of occupation beginning about 2,300 years ago, while rock shelters at Eagle Bluff and on the Zuytdorp Cliffs are up to 4,600 years old.

The late Pleistocene was characterised by cold glacial and warm interglacial periods. Sea levels rose when glaciers melted, then fell during cold periods when water was locked up in ice. The more recent Holocene has been a warm interglacial period.

Archaeologists believe people may have moved away from Shark Bay during glacial periods when the sea level was lower and fresh water limited. The types of food available would also have been affected by the lower sea levels.

Sea level rises during interglacial periods would have flooded previously occupied sites, making them unsuitable for living and possibly removing evidence of their occupation. There would have been a resurgence of mangroves and shellfish when the sea reached its present level 7,000 to 4,000 years ago.

In 1772 the French explorer Saint-Alouarn saw smoke coming from Dirk Hartog Island and his crew found what they believed was evidence of fires and a ceremonial area on the island.

Two other French expeditions led by Baudin and de Freycinet noted the presence of groups of up to 30 Aboriginal people on Peron Peninsula. Baudin’s expedition naturalist, François Péron, made the first written descriptions of Aboriginal people ever presented to the rest of the world. Drawings depicting campsites and circular, semi-permanent huts accompanied Peron’s descriptions.

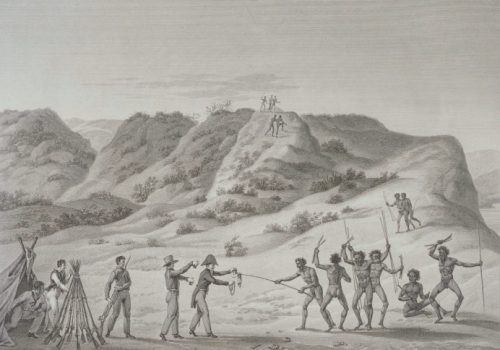

Later, de Freycinet’s artist Jacques Arago recorded a tense encounter between a group of Aboriginal people and some Europeans at Cape Peron. The situation was defused with singing, dancing and an exchange of gifts. Arago wrote: “they watched us as dangerous enemies, and were continually pointing to the ship, exclaiming, ayerkade, ayerkade (go away, go away)”.

In 1858 British surveyor Henry Denham mentioned Aboriginal huts. The encroachment by Europeans into Shark Bay from this time would have seen the beginning of changes to traditional Aboriginal life.

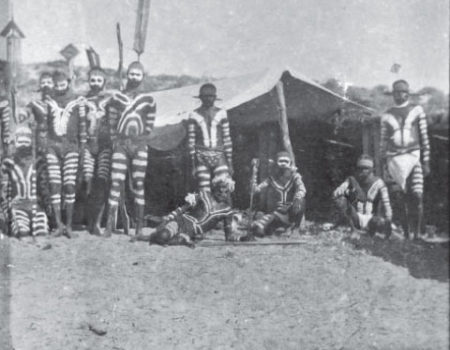

Many Aboriginal men and women worked in the pearling industry which began in the 1850s and peaked in the 1870s. They gathered oysters in the shallows, skin-dived for them, and collected them in wire dredges towed behind sailing boats.

From Shark Bay north to Roebuck Bay and Broome, Western Australia’s early pearling industry was notorious for its ill-treatment of Aboriginal people. Most were not paid wages, just given basic foodstuffs, tobacco and a set of clothes.

Some Aboriginal workers were taken by force. While this mainly occurred in the far north, some Aboriginal people may have been held on Fauré Island. When the pearling season was over in the far north some workers were put ashore in the traditional country of rival tribes and forced to make their own way home.

After introduction of the Pearling Act of 1870 a government official sent to Shark Bay in 1873 reported: “I am satisfied that the Aboriginal natives are as a rule well-treated by their employers…” However, living conditions in the pearlers’ camps were poor and many workers died of dysentery and other diseases.

The pearling industry also recruited Chinese and Malay workers. Many of the Malay workers were actually from Indonesia, the Philippines and Pacific Islands. By the 1900s these groups had become integrated with the Aboriginal inhabitants, creating an interesting ethnic mix still evident today.

Intimate knowledge of their country made Aboriginal people essential to the pastoral industry when it began in the late 1860s with the introduction of sheep. Aboriginal people were employed to patrol station boundaries, crutch and shear sheep, trap dingoes and foxes, repair mechanical equipment, build fences and yards, sink wells, and break in horses.

Fishing has remained important to local Aboriginal people through the years and now ecotourism provides opportunities to show their traditional country to visitors and raise awareness of and respect for the nature of Shark Bay.

Aboriginal people did not live on Bernier and Dorre Islands before European settlement but from 1908 to 1918 Lock Hospitals on these islands were used to isolate Aboriginal people thought to have various diseases including leprosy and tuberculosis.

The patients and their families often had little idea where they were or why they were taken from their traditional country. Men were taken to a hospital on Bernier Island and women to one on Dorre Island. Patients who were fit enough hunted, fished and worked to build and maintain the hospitals.

Hospital records were poorly kept but about a third of the patients admitted to the lock hospitals are thought to have died on the islands. During an anthropological expedition in 1910–1911 social worker Daisy Bates described the hospitals as “tombs of the living dead”.

Hospital admissions decreased after 1913 due to administration costs and in 1918 the hospitals were closed and patients relocated to Port Hedland.

In 1986 the Lock Hospitals were registered as protected areas under the Aboriginal Heritage Act. The islands’ heritage significance was also recognised with their inclusion on the Register of the National Estate in 1987.

Aboriginal communities, particularly the people of Carnarvon, have established memorials on the islands to those that suffered and died there.

The Shark Bay area is significant to Aboriginal people because of their long history of caring for Country, and because of their cultural obligations to understand and care for the area. Caring for country is about protecting important sites and the connections between sites, people and environment.

The ties Aboriginal groups have to land are recognised by Native Title, a form of land title determined by the Federal Court upon application by indigenous people. There are three claimant groups in this region; the Malgana, Nanda and Gnulli. Of these, the Malgana and Nanda people’s claim was determined in 2018. Malgana were granted native title over 28,800 square kilometres of land in the Shark Bay area including a large part of the World Heritage Area and the Nanda determination included the southern portion of the World Heritage Area. The Gnulli native title claim has yet to be determined.

The Parks and Wildlife Service acknowledges the understanding and ties of Aboriginal people to their lands and the potential mutual benefits for conservation of working together with Aboriginal people to care for the land.

In Shark Bay, Malgana people are represented by the Malgana Aboriginal Corporation. Together with Parks and Wildlife Services, they have collaborated on several conservation management projects with numerous benefits including dugong and turtle research, a major Dirk Hartog Island clean-up funded by Coastwest, and interpretive projects. Malgana were successful in being awarded funding for the State Government’s Aboriginal Ranger Program in 2018 and 2019, an acknowledgement of their strong desire to be directly involved in managing the vast conservation estate in the Shark Bay area.

The State Government’s ‘Plan for Our Parks’ initiative was launched in July 2019 to establish new conservation reserves, create more opportunities for nature-based and cultural tourism, provide enhanced biodiversity conservation and build on Aboriginal joint management.

These initiatives create local economic, training and employment opportunities, as well as generating environmental and cultural outcomes.

Learn some of the local Malgana language.

About 250 different Aboriginal languages were spoken when Europeans first settled in Australia, including three in the Shark Bay region: Malgana, Nanda and Yingkarta. Unfortunately European settlement resulted in many Aboriginal languages not being used regularly.

- Malgana is the traditional language of the people of central Shark Bay. Although the last known fluent speakers of Malgana died in the 1990s the language is being revived and is used in community projects, government information, interpretive materials and local ecotourism ventures. Vocabulary is also taught in the local school. This revival has been achieved with the assistance of the Yamaji Language Centre in Geraldton.

- Nanda is the traditional language of Aboriginal people occupying the coastal strip from southern Shark Bay down to Kalbarri. Only a handful of people now speak the language.

- Yingkarta is the traditional language of Aboriginal people whose country stretches along the coast between the Gascoyne and Wooramel Rivers, and some way inland. Today the few people who speak Yingkarta live in Carnarvon.

Language is both a mirror and a vehicle for culture and provides insight into Malgana cultural life. Following is a list of Malgana words and their English translations:

People

Yamaji – Aboriginal person

Yadgalah, yajala – friend

Nyarlu – woman

Gardu – man

Wurrinyu – girl, young woman

Gugu, yamba – boy

Wiyabandi – young man

Bilyunu –baby

Guyu – father

Nanga – mother

Gurda – brother

Yiba – sister

Gantharri – grandchile, grandparent

Warlu – lover, boyfriend/girlfriend, spouse

Terrestrial

Baba – rain, water

Yalgari – tree

Ngaya – wattle

Yudu – bushl, scrub

Jalyanu – grass

Birlirung – everlasting daisy

Walgu – sandalwood fruit and tree

Bangga, barnka – goanna

Thayadi, thayirri – snake

Jabi – small dragon lizard

Migarda – thorny devil

Marlu – small kangaroo species

Yawarda – larger kangaroo species

Biyagu – galah

Garlaya, yalibidi – emu

Marine

Wirriya – sea, salt water

Buthurru – sand

Thalganjangu – lagoon

Mardirra – pink snapper

Mulgarda – mullet

Mulhagarda – whiting

Irrabuga – bottlenose dolphin

Thaaka – shark

Buyungurra – turtle

Wuthuga – dugong

Warda – pearl

Jurruna – pelican

Wanamalu – cormorant

Wabagu – sea eagle

Winthu – wind

Places

Gutharraguda – two waters / two bays – Shark Bay

Wirruwana – Dirk Hartog Island

Wulyibidi – Peron Peninsula

Thaamarli – Tamala Station

Wilyamaya – tip of Heirisson Prong

Adapted from: Malgana Wangganyina (Talking Malgana): an Illustrated Wordlist of the Malgana Language of Western Australia. Mackman, Doreen (ed). Geraldton: Yamaji Language Centre 2003. Copies can be purchased from:

The Yamaji Language Centre

22 Sanford Street (PO Box 433)

Geraldton WA 6531

Australia

Tel: +61 (08) 9964 3550

Fax: +61 (08) 9964 4690