Pearling

The Shark Bay pearl oyster, Pinctada albina, spawned a rush not unlike the gold rushes of the 1800s. Sought after were small straw-coloured ‘seed’ pearls favoured in Asian markets, and pearl shell used to make buttons in the days before plastic fasteners. Pearling began in the 1850s and peaked in the 1870s leaving reminders of the industry all around Shark Bay.

Commercial harvesting began after a government official investigating the guano industry saw potential in Shark Bay’s prolific oyster banks. At low tide shell could be picked by hand or collected by divers, but dredging was the most efficient harvesting technique. This involved dragging wire-meshed baskets over oyster banks behind a shallow-draught, single-mast sailing boat. About 80 boats were working the banks of Shark Bay by 1873.

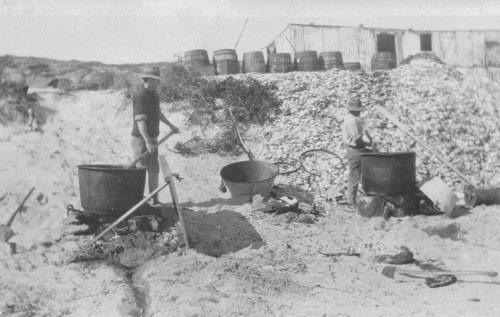

Men collected oysters while women and children cleaned the shells and put the inedible oyster flesh into barrels called ‘pogey pots’. The flesh was left to rot in the sun then boiled until any pearls dropped to the bottom of the pot for collection. The odour was sickening and could be smelled for miles around. There might be just two or three pearls in every hundred shells opened.

The pearl shell was sorted and the best sent to England, France and Germany. Lesser-grade shell was discarded or put to novel use.

The town of Denham was once a large pearlers’ camp called Freshwater Camp and its streets were paved with iridescent mother-of-pearl.

In the rush for riches many European entrepreneurs forced Aboriginal people to labour alongside indentured Chinese, Pacific Islander and ‘Malay’ workers. Treated like slaves the workers suffered terribly and those promised wages did not always receive them. Some Chinese pearlers brought their own vessels and operated in direct competition with the Europeans, causing resentment and conflict.

Some men drowned while diving or when boats sank, and two were killed in a cyclone. Camps were mainly tents and corrugated iron huts harbouring dysentery and other diseases. Many pearlers are buried on the sand dunes behind the beach at Willyah Mia.

The industry ended as once-prolific banks were stripped bare and plastic buttons were introduced in the 1920s and 30s. Many old pearling cutters were then pressed into service as fishing boats as they were useful for net fishing in shallow water.

The wild pearl oyster is now recovering on the banks scraped by the dredges so many years ago while cultured pearls are commercially cultivated in Red Cliff Bay near Monkey Mia.