Contact & Change

In 1772 the French explorer Saint-Alouarn saw smoke coming from Dirk Hartog Island and his crew found what they believed was evidence of fires and a ceremonial area on the island.

Two other French expeditions led by Baudin and de Freycinet noted the presence of groups of up to 30 Aboriginal people on Peron Peninsula. Baudin’s expedition naturalist, François Péron, made the first written descriptions of Aboriginal people ever presented to the rest of the world. Drawings depicting campsites and circular, semi-permanent huts accompanied Peron’s descriptions.

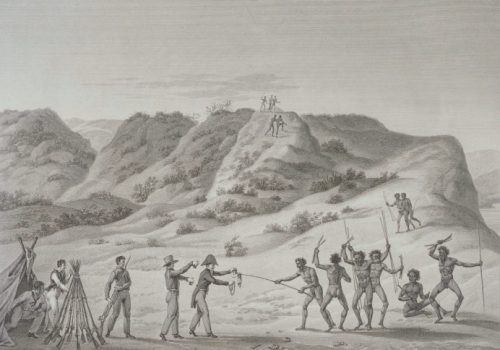

Later, de Freycinet’s artist Jacques Arago recorded a tense encounter between a group of Aboriginal people and some Europeans at Cape Peron. The situation was defused with singing, dancing and an exchange of gifts. Arago wrote: “they watched us as dangerous enemies, and were continually pointing to the ship, exclaiming, ayerkade, ayerkade (go away, go away)”.

In 1858 British surveyor Henry Denham mentioned Aboriginal huts. The encroachment by Europeans into Shark Bay from this time would have seen the beginning of changes to traditional Aboriginal life.

Many Aboriginal men and women worked in the pearling industry which began in the 1850s and peaked in the 1870s. They gathered oysters in the shallows, skin-dived for them, and collected them in wire dredges towed behind sailing boats.

From Shark Bay north to Roebuck Bay and Broome, Western Australia’s early pearling industry was notorious for its ill-treatment of Aboriginal people. Most were not paid wages, just given basic foodstuffs, tobacco and a set of clothes.

Some Aboriginal workers were taken by force. While this mainly occurred in the far north, some Aboriginal people may have been held on Fauré Island. When the pearling season was over in the far north some workers were put ashore in the traditional country of rival tribes and forced to make their own way home.

After introduction of the Pearling Act of 1870 a government official sent to Shark Bay in 1873 reported: “I am satisfied that the Aboriginal natives are as a rule well-treated by their employers…” However, living conditions in the pearlers’ camps were poor and many workers died of dysentery and other diseases.

The pearling industry also recruited Chinese and Malay workers. Many of the Malay workers were actually from Indonesia, the Philippines and Pacific Islands. By the 1900s these groups had become integrated with the Aboriginal inhabitants, creating an interesting ethnic mix still evident today.

Intimate knowledge of their country made Aboriginal people essential to the pastoral industry when it began in the late 1860s with the introduction of sheep. Aboriginal people were employed to patrol station boundaries, crutch and shear sheep, trap dingoes and foxes, repair mechanical equipment, build fences and yards, sink wells, and break in horses.

Fishing has remained important to local Aboriginal people through the years and now ecotourism provides opportunities to show their traditional country to visitors and raise awareness of and respect for the nature of Shark Bay.